The Failure Taxonomy: How Harm Emerges Without Malice - Why most disasters are not caused by bad people — but by predictable system drift

This paper introduces the Failure Taxonomy — a structural model showing how harm accumulates in complex systems through drift, signal loss, and accountability inversion, without anyone intending it.

Dr Alwin Tan, MBBS, FRACS, EMBA (University of Melbourne), AI in Healthcare (Harvard Medical School)

Senior Surgeon | Governance Leader | HealthTech Co-founder |Harvard Medical School — AI in Healthcare |

Australian Institute of Company Directors — GAICD candidate

University of Oxford — Sustainable Enterprise

Institute for Systems Integrity (ISI)

Introduction

When large systems fail, the first instinct is to look for wrongdoing. Someone must have been careless, incompetent, or unethical. Yet time after time, independent inquiries reveal something more troubling: the people involved were often capable, conscientious, and trying to do the right thing.

What failed was not their character.

What failed was the system that shaped their choices.

This paper introduces the Failure Taxonomy — a structural model that explains how harm accumulates in complex organisations without anyone intending it. It builds on the Institute’s earlier analyses of Decision-Making Under System Stress, Why Oversight Fails Under Pressure, and Integrity Is a System Property, and sits within the Systems Integrity Cascade.

Why harm so often appears “unexpected.”

High-risk systems — healthcare, aviation, finance, infrastructure, digital platforms — operate under continuous pressure. Targets tighten. Volumes rise. Resources thin. Under these conditions, organisations adapt. Those adaptations are usually sensible in the moment.

Over time, however, the system drifts beyond the conditions it was designed to operate within. This phenomenon — known in safety science as drift — is not recklessness, but survival under pressure (Rasmussen, 1997; Dekker, 2011).

This is why disasters so often appear to come “out of nowhere”. The conditions that produced them have been accumulating quietly for years.

The Failure Taxonomy

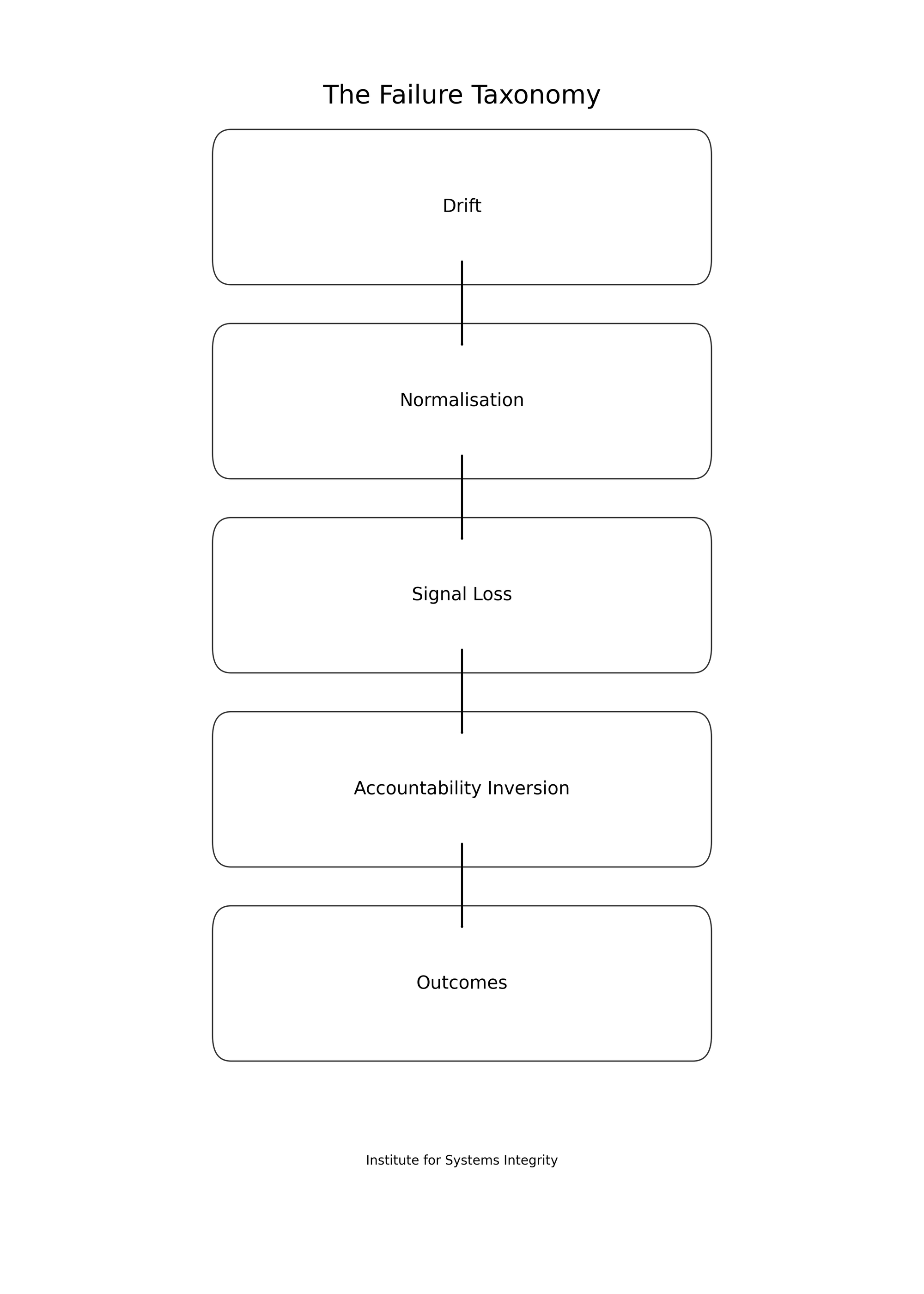

The Failure Taxonomy is a derived framework from the Systems Integrity Cascade. It makes visible the internal pathway by which stressed systems migrate from normal operation to harmful outcomes.

Drift → Normalisation → Signal Loss → Accountability Inversion → Outcomes

This is not a moral sequence.

It is a structural one.

Drift

Small deviations from designed practice accumulate quietly. Workarounds appear so people can keep doing their jobs under pressure.

Because these workarounds solve immediate problems, they are rewarded. Over time, the system’s real operating mode diverges from what policies, procedures, and audits assume is happening (Cook, 1998; Rasmussen, 1997).

No one decides to make the system unsafe.

It simply adapts beyond its limits.

This dynamic was described in Decision-Making Under System Stress: people do what they must to cope when demand exceeds capacity.

Normalisation

Once workarounds keep the system functioning, they become accepted practice. What was once exceptional becomes routine.

Risk is no longer seen as risk.

It becomes “how we do things here”.

This process — known as the normalisation of deviance (Vaughan, 1996) — explains why unsafe conditions can persist in organisations that appear stable and well-managed.

⚙️ Framework — Failure Taxonomy (derived view)

The Failure Taxonomy is a derived framework from the Systems Integrity Cascade.

It is closely related to the Oversight Blindness Pathway, which shows how system stress causes governance to lose visibility.

Signal loss

As drift becomes normal, warning signals fade.

Near-misses go unreported.

Dashboards smooth out variation.

Escalation weakens.

This is the same phenomenon analysed in Why Oversight Fails Under Pressure: under load, information flows become compressed and filtered, and governance becomes blind to emerging risk.

Oversight remains formally in place — but it no longer reflects reality.

Accountability inversion

When outcomes begin to deteriorate, responsibility flows downward.

Frontline staff carry the blame.

Leadership remains insulated from the conditions that created the risk.

This inversion is not malicious. It is structural.

It reflects misalignment between authority, accountability, and information, as analysed in Integrity Is a System Property and formalised in the Integrity Alignment Lens.

Outcomes

By the time harm becomes visible, the pathway that produced it is already deeply embedded.

The system responds with:

- investigations

- disciplinary action

- new rules

But these arrive after damage has occurred. They treat symptoms rather than the structural pathway that created them.

The outcome was not a surprise.

It was the end of a long, quiet sequence.

Why this matters

The Failure Taxonomy explains why many of the most damaging institutional failures of recent decades — from aerospace and healthcare to financial services and public administration — did not require corruption or cruelty.

They required:

- sustained pressure

- blind oversight

- misaligned authority and accountability

- and time

Waiting for misconduct is therefore too late.

By the time wrongdoing is visible, the system has already failed.

Conclusion

Harm does not need bad people.

It needs drift without visibility, pressure without governance, and accountability without authority.

The Failure Taxonomy gives boards, regulators, and institutions a way to see danger before it becomes irreversible — and to treat integrity as a matter of system design, not moral hope.

Related ISI work

- Decision-Making Under System Stress

- Why Oversight Fails Under Pressure

- Integrity Is a System Property

- The Systems Integrity Cascade

- The Oversight Blindness Pathway

- Integrity as a System Property — Framework

References (Harvard style)

Cook, R.I. (1998). How Complex Systems Fail. Chicago: Cognitive Technologies Laboratory.

Dekker, S. (2011). Drift into Failure: From Hunting Broken Components to Understanding Complex Systems. Farnham: Ashgate.

Hollnagel, E. (2014). Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management. Farnham: Ashgate.

Rasmussen, J. (1997) ‘Risk management in a dynamic society’, Safety Science, 27(2–3), pp. 183–213.

Reason, J. (1997). Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Vaughan, D. (1996). The Challenger Launch Decision. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weick, K.E. and Sutcliffe, K.M. (2007). Managing the Unexpected. 2nd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.