Decision-Making Under System Stress: Why Good People Make Predictably Weaker Decisions — and What Integrity Requires

Dr Alwin Tan, MBBS, FRACS, EMBA (University of Melbourne), AI in Healthcare (Harvard Medical School)

Institute for Systems Integrity

Introduction: the limits of individual explanations

When adverse outcomes occur, organisations often focus first on individual actions.

Questions such as who made the wrong decision or who failed to follow the process are common starting points for internal reviews and investigations.

While individual actions matter, research from human factors and decision-science literature consistently shows that decision quality is strongly shaped by the conditions under which decisions are made. Under sustained system stress, decision-making tends to degrade in predictable and well-documented ways (Staal, 2004; Phillips-Wren and Adya, 2020).

Harm, in these contexts, does not require incompetence or ill intent. It can emerge when systems systematically constrain attention, time, and information, thereby shaping how decisions are made.

From a systems-integrity perspective, the critical issue is not whether individuals tried hard enough, but whether the system preserved the conditions necessary for sound decision-making.

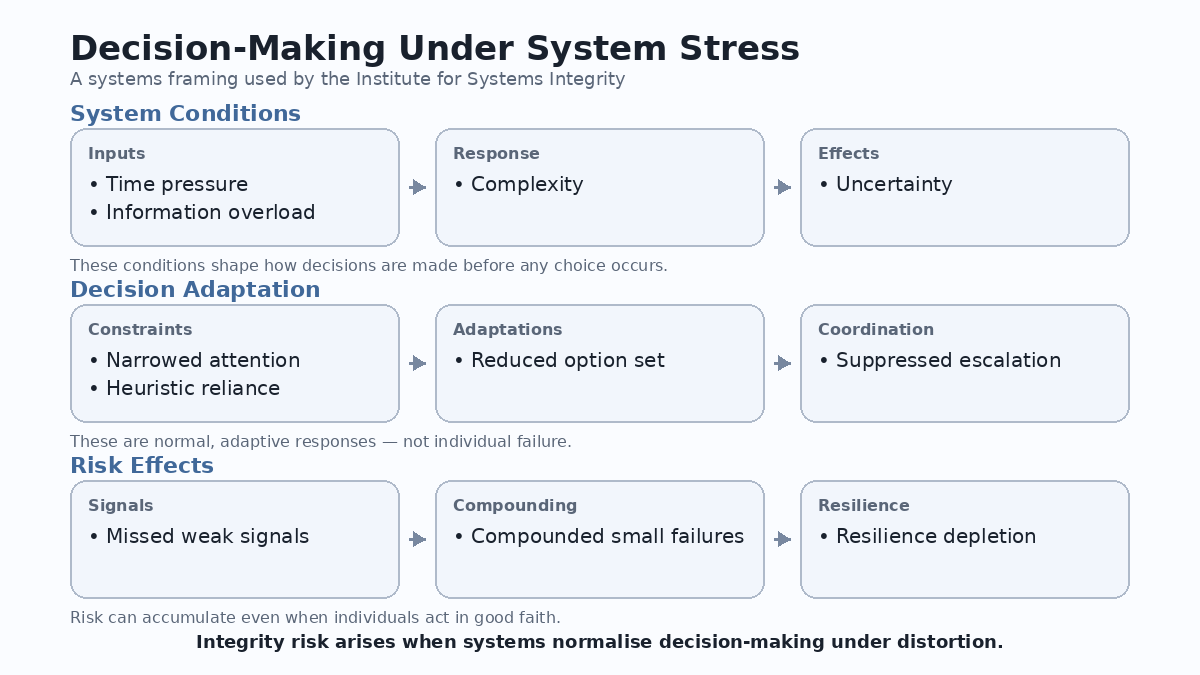

This article examines one segment of the Systems Integrity Cascade — link: decision-making under system stress.

What is meant by “system stress”

In the decision-science literature, stress is not defined simply as workload or busyness.

Phillips-Wren and Adya (2020) identify four interacting “decision stressors” that are repeatedly associated with degraded decision quality:

- Time pressure — decisions must be made before sufficient sense-making can occur

- Information overload — the volume or complexity of information exceeds processing capacity

- Complexity — multiple interacting variables with unclear or non-linear relationships

- Uncertainty — incomplete, ambiguous, or rapidly changing information

Under these conditions, cognitive processing adapts. Experimental and naturalistic studies show that decision-makers narrow attention, reduce the number of options considered, and rely more heavily on experience-based pattern recognition rather than deliberate analysis (Staal, 2004; Klein, 1998).

These adaptations are normal human responses, not evidence of poor capability.

Problems arise when organisations depend on these adaptive modes as a routine operating state, rather than as short-term responses to exceptional circumstances.

Decision distortion as an expected effect

Under sustained exposure to decision stressors, research describes several recurring shifts in decision behaviour, including:

- prioritisation of immediate task completion over longer-term risk considerations

- selection of the first acceptable option rather than comparison of alternatives

- early closure of decision processes

- reduced escalation or consultation

- increased reliance on informal workarounds

These patterns are not pathological. They are functional responses to constrained environments (Staal, 2004; Klein, 1998).

In applied settings such as healthcare, qualitative studies and incident analyses describe how these shifts may manifest as compressed handovers, deferred discussions, or informal compensatory actions intended to maintain service continuity (Reale et al., 2023).

From outside the system, such actions may later be interpreted as poor judgment. From within the system, they are often experienced as necessary trade-offs made under constraint.

Integrity risk: retrospective judgment under unrealistic assumptions

A recurring integrity risk arises when organisations:

- design environments characterised by chronic time pressure and overload

- Relies on adaptive human behaviour to maintain output

- , retrospectively assess decisions using standards that assume stable, well-resourced conditions

This creates a structural mismatch between how decisions were actually made and how they are later evaluated.

The resulting harm is not limited to operational outcomes. Research on moral injury suggests that repeated exposure to situations where professionals cannot meet their own standards — despite acting in good faith — can have lasting psychological and organisational consequences.

From an integrity standpoint, a more appropriate evaluative question is:

What options were realistically available to decision-makers at the time?

A constrained ISI framing

For clarity and analytical discipline, the Institute for Systems Integrity uses the following minimal framing:

System stressors → Decision distortion → Increased risk of harm

- System stressors

Time pressure, information overload, complexity, uncertainty - Decision distortion

Narrowed attention, heuristic reliance, reduced coordination - Risk of harm

Missed weak signals, accumulation of small failures, erosion of system resilience

This framing does not eliminate individual responsibility. It re-locates accountability so that system conditions are examined alongside individual actions.

Implications for leadership and governance

Several implications follow directly from the evidence:

- Persistent error rates may indicate chronic stress, not isolated failure

- Human resilience is finite and can be depleted without obvious warning signs

- Oversight that focuses only on outcomes may miss early indicators of decision degradation

Leaders and boards concerned with integrity should therefore ask:

- Where are decision-makers consistently operating under time or information constraints?

- Which safeguards or buffers have been removed to improve efficiency?

- Which “near misses” indicate narrowing margins rather than success?

These questions focus attention on conditions, not just results.

Conclusion: Integrity as a system property

Decision-making under stress should not be treated as a test of character.

It is a test of system design.

If adverse outcomes are repeatedly attributed to individual failure while underlying decision conditions remain unchanged, similar outcomes should be expected to recur.

From a systems-integrity perspective, integrity is demonstrated not by retrospective compliance, but by whether systems enable sound decisions to be made under realistic operating conditions.

This article forms part of the Institute for Systems Integrity’s foundational work on decision-making, governance, and systemic risk.

How to cite this paper

Institute for Systems Integrity (2026).

Decision-Making Under System Stress: Why Good People Make Predictably Weaker Decisions — and What Integrity Requires.

-https://www.systemsintegrity.org/decision-making-under-system-stress/

References (Harvard style)

Phillips-Wren, G. and Adya, M. (2020) ‘Decision making under stress: the role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty’, Journal of Decision Systems, 29, pp. 213–225.

Staal, M.A. (2004). Stress, Cognition, and Human Performance: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. NASA/TM-2004-212824.

Reale, C. et al. (2023) ‘Decision-making during high-risk events: a systematic literature review’, Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making.

Klein, G. (1998). Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

© 2026 Institute for Systems Integrity. All rights reserved.

Content may be quoted or referenced with attribution.

Commercial reproduction requires written permission.