Beyond Legality: Why Boards Must Ask “Should We?

Governance failures rarely stem from illegality. More often, they arise from lawful, compliant decisions that prove strategically or ethically unsound. This ISI paper explores why boards must move beyond “Can we?” and institutionalise the discipline of asking “Should we?”.

Dr Alwin Tan, MBBS, FRACS, EMBA (University of Melbourne), AI in Healthcare (Harvard Medical School)

Senior Surgeon | Governance Leader | HealthTech Co-founder |Harvard Medical School — AI in Healthcare |

Australian Institute of Company Directors — GAICD candidate |

University of Oxford — Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment (Sustainable Enterprise)

An Institute for Systems Integrity (ISI) Perspective

Executive Summary

Governance failures rarely originate from illegal decisions.

More commonly, they arise from decisions that were:

• Lawful

• Technically compliant

• Formally approved

…yet strategically, ethically, or reputationally unsound.

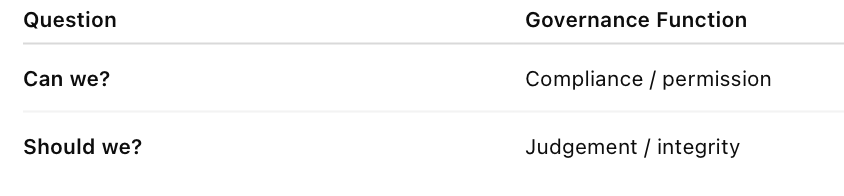

This paper examines the distinction between “Can we?” — a question of permission — and “Should we?” — a question of judgement. While legality defines the boundary of compliance, integrity defines the boundary of defensibility, legitimacy, and long-term organisational stability.

Modern governance requires boards to govern beyond legality alone.

1. The Limits of Legality

Legality is a necessary foundation of governance.

It answers a critical but narrow question:

Is this decision permitted under law and regulation?

Compliance frameworks are designed to prevent breaches.

They are not designed to guarantee:

• Fairness

• Ethical soundness

• Reputational resilience

• Stakeholder legitimacy

A decision may satisfy legal requirements yet still expose the organisation to material harm.

2. The Governance Gap

Investigations into major organisational failures repeatedly reveal a consistent pattern:

✔ Legal clearance obtained

✔ Policy compliance satisfied

✔ Risk assessments completed

Yet:

✖ Stakeholder harm occurred

✖ Trust eroded

✖ Reputation damaged

✖ Regulatory intervention followed

The deficiency is rarely legality.

The deficiency is judgment.

The APRA Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia identified this gap explicitly, noting a recurring failure to distinguish between what the organisation could do and what it should do (APRA 2018).

3. “Can We?” versus “Should We?”

“Can we?” governs technical permissibility.

“Should we?” governs:

• Consequences

• Defensibility

• Stakeholder impact

• Reputational exposure

• System effects

• Long-term sustainability

Both questions are essential.

Only one is sufficient.

4. Why Permission Logic Dominates

Organisations naturally default toward “Can we?” due to structural factors.

4.1 Measurability Bias

Compliance outcomes are binary and auditable.

Judgment outcomes are contextual and evaluative.

4.2 Incentive Asymmetry

Performance systems often reward:

• Speed

• Growth

• Optimisation

• Revenue outcomes

Integrity failures emerge later and diffuse across stakeholders.

4.3 Accountability Diffusion

Permission decisions feel procedurally shared.

Judgment decisions carry perceived personal exposure.

5. The Governance Function of “Should We?”

“Should we?” functions as a stability and legitimacy filter.

It evaluates whether a lawful decision may:

• Introduce reputational fragility

• Generate conduct risk

• Erode stakeholder trust

• Distort organisational culture

• Create regulatory backlash

• Produce long-term strategic harm

Within ISI’s Integrity Protection Stack, legality governs compliance boundaries, while integrity governs systemic sustainability.

6. Alignment with Contemporary Governance Frameworks

The obligation to govern beyond legality is embedded within established governance principles:

• ASX Corporate Governance Principles — entities must act lawfully, ethically, and responsibly (ASX CGC 2019)

• OECD Principles of Corporate Governance — ethical standards extend beyond compliance (OECD 2015)

• APRA Prudential Inquiry (CBA) — failure to distinguish “Can we?” vs “Should we?” identified as a governance weakness (APRA 2018)

• Hayne Royal Commission — reinforced that compliance with legal form alone does not ensure outcomes aligned with fairness and community expectations (Hayne 2019)

The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) similarly emphasises that directors govern not only compliance, but judgment, ethics, culture, and long-term performance sustainability (AICD n.d.).

7. Integrity as a Governance Obligation

Boards are stewards of:

• Organisational sustainability

• Reputational capital

• Stakeholder trust

• Cultural tone

• Long-term value creation

This stewardship requires judgment beyond legal permissibility.

Legality protects against prosecution.

Integrity protects against collapse.

8. Operationalising “Should We?”

To avoid reducing integrity to rhetoric:

8.1 Formalise Integrity Criteria

Define fairness, defensibility, stakeholder impact, and reputational considerations.

8.2 Establish Escalation Triggers

Lawful yet ethically or reputationally ambiguous decisions → structured review.

8.3 Protect Constructive Dissent

Effective judgement requires psychological safety.

8.4 Document Decision Rationale

Traceability strengthens defensibility.

9. Strategic Value of Judgement-Centred Governance

Institutionalising “Should we?” strengthens:

✔ Reputational resilience

✔ Conduct risk management

✔ Cultural stability

✔ Stakeholder legitimacy

✔ Regulatory trust

✔ Decision durability

Conclusion

Governance systems designed solely around legality govern permission.

Governance systems incorporating integrity govern sustainability.

Boards that consistently ask “Should we?” enhance organisational stability, legitimacy, and long-term resilience.

References (Harvard Style)

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) 2018,

Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA): Final Report, APRA.

ASX Corporate Governance Council (ASX CGC) 2019,

Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations, 4th edn, ASX.

Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) n.d.,

Corporate Governance Framework, AICD.

Hayne, KM 2019,

Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry: Final Report, Commonwealth of Australia.

OECD 2015,

G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, OECD Publishing.

Institute for Systems Integrity (ISI) 2026.,

Integrity Protection Stack.

Institute for Systems Integrity (ISI) 2026,

Oversight Blindness.

Institute for Systems Integrity (ISI) 2026.,

The Pause Principle.